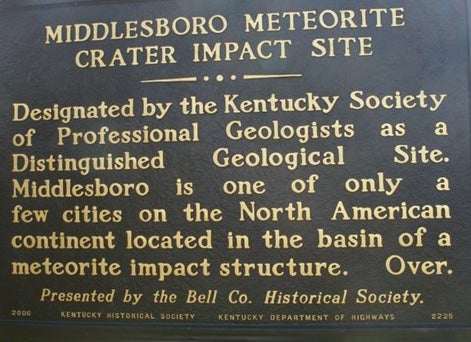

The story behind the crater

Published 2:14 pm Thursday, February 2, 2023

BY JORDAN BROOKS

jordan.brooks@middlesboronews.com

The unique development of a circular, topographic depression that is part of the Appalachian Plateau, known as the Middlesboro Basin, has helped shape the history of the Middlesboro and Cumberland Gap region. Arguably, of all the visitors to Middlesboro, the one that has made the biggest impact came to the area long before Dr. Thomas Walker or Daniel Boone. It has had a greater impact on the area than all of the soldiers of the Confederate and Union armies combined, and is more responsible for the current layout of Middlesboro than Alexander Arthur, the city’s founder.

Looking over Middlesboro, standing on the overlook of Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, one might notice the city sits in what appears to be a bowl-shaped depression.

It is the large depression itself that is unusual, out of place and the result of a visit almost 300 millions years ago by a traveler out of this world.

“Geologists visiting the area in the early years of the last century noted that the rock strata or layers in what came to be known as the Middlesboro Basin had experienced extensive faulting and folding,” said Jes’Anne Givens, director of the Bell County Historical Society. According to Givens, early geologists attributed the Middlesboro faulting to stresses produced by the formation of the Appalachian Mountains that occurred hundreds of millions of years ago.

In the 1960s geologists looked at the faulting and folding of the rocks of the Middlesboro Basis again and came to a new conclusion as to the origin of the rock structures they observed. It was observed that they were not long, linear faults, but rather arc-like or circular in nature surrounding the area which encompasses the city. It was also noted that in the center of the basin a large amount of material had been uplifted from below.

“The evidence that led geologists to contemplate the true origin of the Middlesboro Basin came with the discovery of ‘shocked quartz,’” said Givens.

Shocked quartz occurs when extreme pressure is applied to the lattice of molecules that make up the mineral quartz. This pressure causes the lattice to shift ever so slightly, but enough to make it a different form of quartz.

The catch was that shocked quartz only occurs in two places: at the bottom of craters after the explosion of a nuclear bomb, and at the bottom of impact craters from meteorites. The final clue in determining the origin of the Middlesboro basin came in the discovery of “shatter cones.”

“They’re cone-shaped rock fragments that are produced when rocks are exposed to high pressure, high velocity shock waves,” said Givens.

Shatter cones, like shocked quartz, are only found in craters left after a nuclear explosion or in meteor impact craters.

Geologists looking at the accumulated evidence concluded that the Middlesboro Basin was formed by the impact of a large meteor strike 300 million years ago.

The crater itself is large, at about 3.5 miles in diameter, it speaks to the tremendous amount of energy that was released at impact.

“While no evidence of the impacting object remains, it was probably around 700 feet, or a little over two football fields in diameter,” said Givens. “At impact it would have released energy 5,000 times greater than that of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima at the end of WWII.”

The blast wave from the impact would have radiated outward in all directions at supersonic speeds. Earthquakes have been felt across the region, and more importantly, most all living creatures within a 20-mile radius probably would have been killed.

On average, an impact such as the one that caused this great depression happens every 10,000-15,000 years. To date, approximately 150 impact sites have been identified, ranging in size from 50 feet to over 180 miles in diameter, and some dating back nearly 2 billion years.

Native Americans, explorers, miners and tourists alike have traveled through the Cumberland Gap area and not realized the significance of the very ground beneath their feet and the catastrophic story that it tells.

Scientists say it isn’t a question of if the Earth will be hit again, but when. The odds of getting hit again are like rolling the dice, but in the meantime, scientists use natural wonders such as the basin to determine just how much the past can help us in the future.