Early settlers along Wilderness Road: Part 5

Published 4:07 pm Tuesday, December 13, 2022

JADON GIBSON

Contributing columnist

The Revolutionary War ended with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781.

Indian attacks were expected to cease as well but did not. Rye Cove was one of the focal points of Indian attacks.

In the summer of 1787 the Indians attacked the home of John Carter of Rye Cove.

Carter had set out to listen for the bells of his cattle and horses. He soon heard his wife yell.

He was unarmed so he had no choice but to flee. He returned with a company of men to find his house in flames, his wife and six children dead.

The following spring a band of Indians invaded Rye Cove and attacked Carter’s Fort, capturing two sons of Thomas Carter and a slave. Eventually they were freed but there were other such attacks that led to deaths.

Daniel Boone’s reputation grew during this period of Indian uprisings. He became known as the hero of Clinch Valley because of his diligence and bravery.

Joseph Martin and his party were the first white settlers in Powell arriving there in 1769. It wasn’t long before they were repelled by Indians. Martin reorganized and returned in 1775 but the Indians remained sky. Martin was called to help quell their uprisings.

Many settlers abandoned forts in the Clinch-Powell region during this time. Martin’s men were on the brink of leaving Martin’s Station during his absence and left in search of William Parks. They came upon his corpse. He had been murdered and scalped. The men lashed his body to a pole and carried him back to the camp on their shoulders. He is buried in present-day Rose Hill.

They found a messenger waiting for them when they returned to camp. He had a warning from Joseph Martin saying, “the Indians have declared war and were doing a great deal of mischief.”

“The following morning we left for Blackmore’s Fort on the Clinch River,” Captain Redd wrote. “There we found the greater part of the men who had left Mump’s Fort, Priest’s Fort and our station.

“Captain Martin was ordered to Rye Cove where he found a man by the name of Isaac Crisman and two members of his family murdered by the Indians. Martin and his men had to pass through Little Moccasin Gap, a very dangerous passageway in that era. At the gap the trail goes through a very narrow deep gorge in the mountain. The Indians had killed many whites at that location.

“As Captain Martin passed through the gap he had his men spread out making it more difficult for them to be hit by gunfire. Just as the head of his column emerged from the narrow passageway they were fired on by Indians on top of the ridge but the damage was minimal.

One of Martin’s men was killed but another by the name of Bunch had five balls shot through the flesh. Not wanting to engage in combat the Indians immediately ran off after firing at them.”

Stationed on the brink of the Cherokee territory Martin was the first line of defense for the settlements and they were constantly involved in skirmishes with the Indians. He was still a large landowner at the time in what would become Lee County, Virginia.

In the summer of 1776 Martin received a letter from Colonel John Donelson, Andrew Jackson’s future father-in-law. It ordered him to assemble his militia company at the Long Island of the Holston River. Fort Patrick Henry was erected and a campaign was launched against the Cherokee towns including Chilhowee and Chota. Both were burned.

On November 3, 1777, Virginia Gov. Patrick Henry appointed Martin superintendent of Indian Affairs, a post that specified that he must reside within the Indian nation. Although Martin wanted to remain near his land holdings in Powell Valley, he settled on the Long Island of Holston. He ended up taking an Indian “wife” even though his lawful wife, Sarah Lucas Martin remained at home in Henry County, Virginia.

It is recorded that their relationship saved many lives including that of Joseph Martin himself. His Indian wife Betsy Ward was the daughter of Nancy Ward, the most famous Indian woman of the time. Nancy was the niece of Little Carpenter, the “emperor” of the Cherokees. The association resulted in Martin being privy to the Indian grapevine.

Logan, the half-breed renegade, had been a thorn in Martin’s side as he vented his rage in a series of killing sprees of women and children following the massacre of his own family by whites, on Yellow Creek in Ohio. With great jubilation Martin heard that Chief Logan had returned to his northern home.

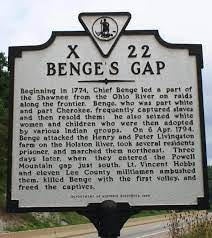

A chill came across Joseph Martin when he heard of the bloody exploits of Chief Benge, another half-breed Indian who was causing havoc in the Clinch-Powell region. Men, women and children were being slaughtered in horrid fashion. Property was being stolen or destroyed. Slaves were being taken and herded north where they were sold. Frightful settlers abandoned forts and stations in Powell Valley in fear.

Benge, a cunning and strong warrior with survival skills second to none, was bent on driving all white men from the region. A little over two centuries ago settlers shuddered upon hearing news of Benge and his marauding band of renegades attacking settlers like themselves. Who would be next? Are Benge and his men skulking about in the woods waiting to strike?

The Indians soon departed without further battle but captured two women, Polly Alley, at Osborn’s Fort, and Jane Whitaker, near Castle’s Woods. They proceeded northward through the “Breaks” where the forks of the Big Sandy River pass through the Cumberland Mountains. They continued until they reached the Ohio River.

The Indians and their prisoners crossed the Ohio River on a raft of logs before finally reaching their destination in present-day Ohio. The prisoners were stripped and painted but were eventually allowed freedom of the village. As time passed they were able to venture outside the village and return and after a month the Indians were less vigilant in watching the prisoners.

One morning Polly and Jane decided conditions were favorable to attempt their escape from the village. They began traveling on a southward bearing and never returned, wandering through the wilderness for a month before finding their way to Pound Gap, a passageway to their home. Their hearts raced with joy as they continued their trek back to folks they knew and loved.

Benge made many raids on settlers in the area of Moccasin Gap. On August 26, 1791, his party attacked the house of Elisha Ferris. His dwelling was on the edge of what is now Gate City. Ferris was killed and his wife (Nancy) and daughter were taken along with a Mrs. Livingston and a young child. All but Nancy Ferris were cruelly murdered during the first day of their captivity.

Editor’s note: When I was a young boy I recall my parents admonishing my brother and I to “be good or the boogey man might get you.” Well, when pioneering families were alone in the dark wilds they substituted, “Be good younguns or Chief Benge will get you.”

Jadon Gibson is a freelance writer from Harrogate. His writings are both historic and nostalgic in nature. Thanks to Lincoln Memorial University, Alice Lloyd College and the Museum of Appalachia for their assistance.