Coming home: Remains of Claiborne County Navy veteran killed at Pearl Harbor finally identified

Published 1:50 pm Friday, July 15, 2022

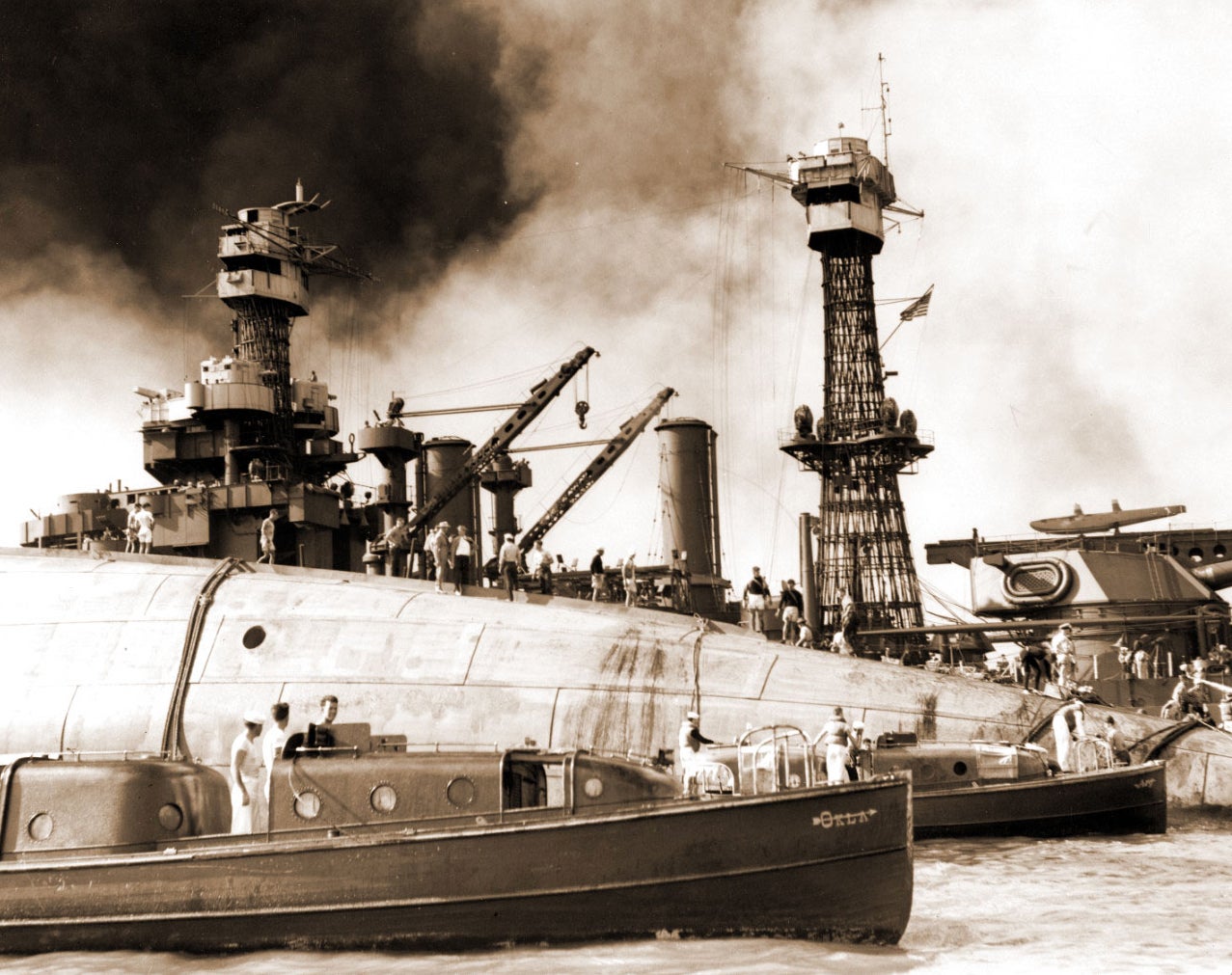

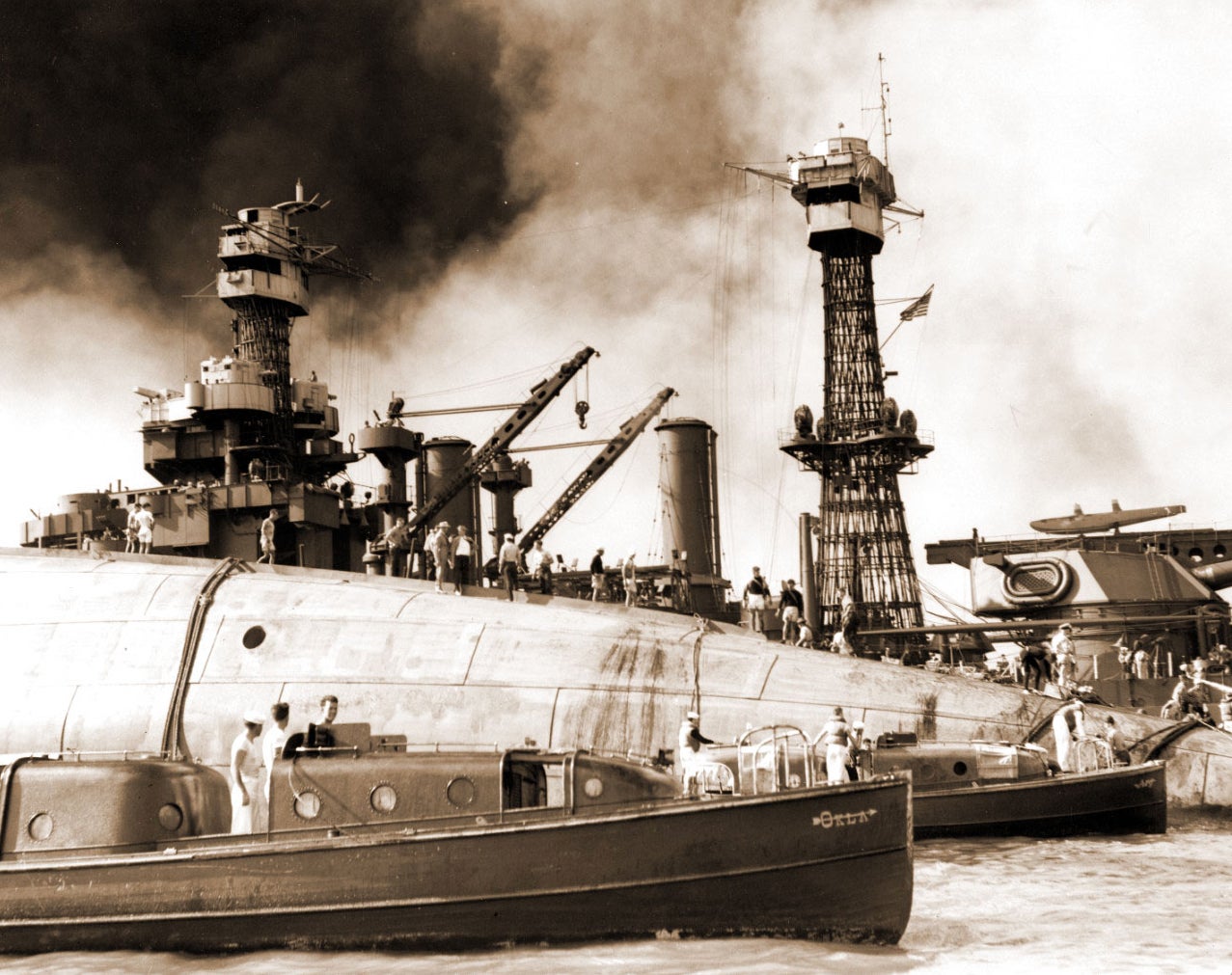

- Sailors work to free those trapped inside the capsized U.S.S. Oklahoma during the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. U.S. Navy photo

JOHN REITMAN

john.reitman@bluegrassnewsmedia.com

After more than 80 years, Seaman First Class William Brooks finally is going home.

A native of Cumberland Gap, Tennessee, Brooks died Dec. 7, 1941 in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that launched the United States into World War II. Brooks served in the U.S. Navy aboard the U.S.S. Oklahoma. The battleship was sunk when several Japanese torpedoes ripped open its port side from stem to stern.

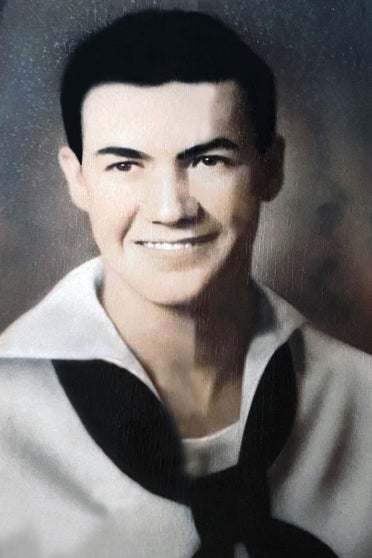

William Brooks

Finally identified by the Navy using cutting-edge DNA matching technology, Brooks will be laid to rest next to his brother in Glen Haven Memorial Park in Glen Burnie, Maryland, where his family now resides. Burial will take place at 11 a.m. on July 16, three days short of what would be his 100th birthday, said Linda Dowling, Brooks’ niece and closest living relative.

Dowling is no stranger to a life of service. She is a retired Russian language linguist for the National Security Agency, and her husband, Drew, is a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point who know gives tours at the U.S. Naval Academy. But when a Marine showed up at her door recently, she was more than a little shocked.

“My dad had given me a 9×12 picture of Uncle Billy,” Dowling said. “I was surprised when (the Marine) told me they had finally identified his remains.”

On the morning of Dec. 7, the Oklahoma’s mooring position outside the U.S.S. Maryland in Pearl Harbor made her an easy target for Japanese torpedo bombers. The ship was hit by as many as eight torpedoes that eventually found their way into the ship’s oil and fuel reserves. Less than 15 minutes after the first torpedo strike, the Oklahoma had rolled over onto her port side with hundreds of her crew, including Brooks, trapped inside.

A total of 2,403 U.S. sailors lost their lives that day, including 429 members of the Oklahoma. As the Navy began to disinter the Oklahoma’s crew, they were able to identify 41 people almost immediately, leaving the remains of 388 unidentified for decades. As technology advanced, early work to identify the crew began in 2009 and took off in 2015.

Using source DNA from families, scientists at labs either at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, and Offutt AFB in Nebraska have been able to identify 355 of the remaining 388 crewmembers, said Eugene Hughes, public affairs representative for Navy Casualty Assistance, which acts as a liaison between the Navy and the families of fallen sailors.

Sailors work to free those trapped inside the capsized U.S.S. Oklahoma during the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. U.S. Navy photo

“This has been the greatest honor of my career to serve these families,” Hughes said.

The final 33 crewmembers of the Oklahoma whose remains were unidentifiable, were laid to rest last Dec. 7, the 80th anniversary of the attack that claimed their lives.

The Navy gave families of the victims the choice of having remains interred at a military cemetery in Hawaii, Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia or at a local cemetery of the family’s choosing.

In Brooks’ case, the family has chosen he be buried near them in Maryland.

“I could have had him buried in Hawaii with all his shipmates,” Dowling said. “Then the Navy told me he wasn’t in Hawaii. He was at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. I said ‘oh, my, that’s pretty cold.’ I thought the right thing to do was bring him to Maryland to be buried next to his brother.

“My dad carried his picture his whole life. Uncle Billy had a special place in dad’s heart. The least I could do was bring him here and give him a proper burial and put him with his brother.”

Although she grew up in Maryland, Dowling remembers spending summers as a child visiting family in Claiborne County. She recalls it was quite a long time after the attack on Pearl Harbor that her grandmother learned Brooks had been killed.

“I remember thinking how awful for her,” Dowling said. “She lost her first husband to cancer in the coal mines, and now she’d lost her son.”

When her uncle’s remains were flown to Maryland in preparation for the funeral, Dowling said she was surprised by the crowd of about 200 who turned out at the airport to pay their respects. Those in attendance included several color guard units and a motorcycle escort.

“It was a very moving moment when that flag-draped coffin came off the plane,” she said. “People in the airport were watching out the windows.”

After the war, Brooks was posthumously award the Purple Heart, Combat Action Ribbon, Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Service Medal (with Fleet Clasp), Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (with Bronze Star), American Campaign Medal and World War II Victory Medal.