Lower health care costs act comes with own price

Published 10:50 am Tuesday, December 17, 2019

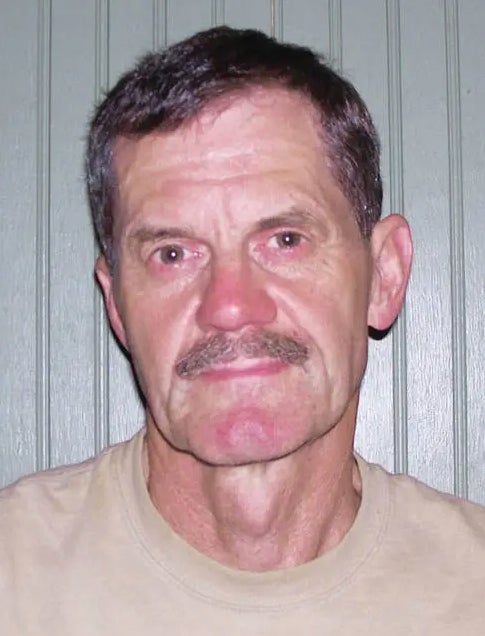

By Josh Crawford

Guest Columnist

On Sunday, Dec. 8, federal lawmakers unveiled the “Lower Health Care Costs Act of 2019” (LHCCA). The bill aims to tackle some of the issues facing the American healthcare system, most notably “surprise billing.”

Surprise billing happens when a patient receives treatment at a hospital covered by their insurance, but part, or all, of the care is carried out by an out-of-network provider contracted with the hospital. As a result, some, or all, of the costs are not covered by your insurance and – Surprise! – you now have a bill you weren’t expecting.

No one wants to get a bill in the mail, especially one they weren’t expecting, but in the case of the “Lower Health Care Costs Act of 2019,” the medicine is worse than the ailment.

The primary method by which the LHCCA would curb surprise billing is through federally mandated price controls or “benchmarking” as it’s referred to in the bill.

The prospect of additional federal price controls in healthcare ought to be cause for concern for lawmakers. Even if price controls do lower costs – because the federal government now says the cost is lower – they cause negative side effects the likes of which would need to be read quickly at the end of a commercial.

Price controls not only limit how much a particular provider can earn for a given service, but can result in doctors and other healthcare providers not being able to continue operations. As Yale Economics Professor Fiona Scott Morton has pointed out, “When prices are held below natural levels, resources such as talent and investor capital leave an industry to seek a better return elsewhere.”

It’s an essential tenet of economics; price controls distort markets and prevent providers from obtaining accurate information about their consumers. Outside of a free-market price system, producers don’t know how much of something to produce and, absent an appropriate profit motive, won’t produce much of anything at all.

In the context of healthcare, this means provider consolidation, less investment in innovation, and less satisfactory care. It is ultimately patients who will bear the cost.

These concerns aren’t just theoretical either. As is often the case, California already implemented similar provisions in 2017.

A study published in August in the American Journal of Managed Care found that while the law did result in fewer surprise bills it also led to “lower provider payment rates and increased physician group consolidation.” Additionally, according to the California Medical Association, “The California Department of Managed Health Care recently reported that there was a 48% increase in patient access to care complaints [from] 2016-2018 – after the passage of California’s surprise billing law.”

That’s particularly concerning for rural states like Kentucky, where many of our residents already have fewer healthcare options and less access to care than states like California. Rural healthcare already faces a myriad of challenges including workforce shortages and geographic isolation, legislation that encourages provider consolidation would only make these problems worse.

That’s why the opposition to these kinds of price controls come from a diverse coalition including American Medical Association, American Hospital Association, and the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Price controls were also opposed in a letter sent to lawmakers from 75 Conservative groups last week, reminding them of the economic scarcity price controls naturally create.

While the issue of surprise medical billing is undoubtedly a problem, federally mandated price controls are not the kind of medicine Congress should prescribe.

Josh Crawford is executive director of the Pegasus Institute.